“WHO IS KILLING Tencent?” was the headline of an article on a Chinese business news site this autumn. Those sharing the link on WeChat, a social-media and payments service that is the crown jewel of the Chinese technology giant, see something else: “This title contains exaggerated and misleading information”. The swap is ostensibly the result of a move by Tencent in April to sanitise content, after a crackdown on popular online platforms by government regulators, but is also self-serving. Scoffing WeChat users circulated the article just to highlight the switch.

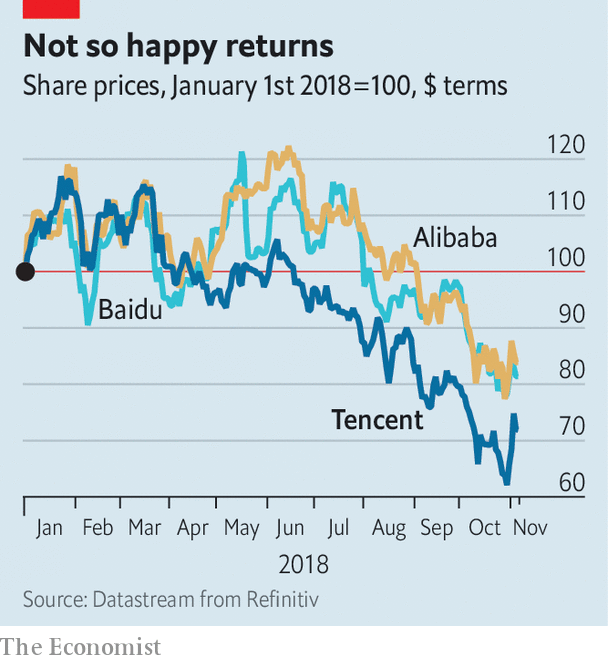

It would be no surprise if Tencent were feeling touchy as it approaches its 20th anniversary on November 11th. Its shares, traded in Hong Kong since 2004, have fallen by 28% in 2018 (see chart). This time last year it was the first Asian company to be worth half-a-trillion dollars, hitting a record valuation in January of $573bn. It has since shed $218bn, roughly equivalent in value to losing Boeing or Intel. Other Chinese internet stocks have fared worse than Tencent, among them NetEase, a gaming rival, and JD.com, an e-commerce firm. But even so, the drop stands out.

The company posted its first quarterly profit decline for nearly 13 years in the three-month period ending in June. A regulatory hold-up that was blocking it from charging for new video games was the chief culprit, it explained. Although it has sprawled into all sorts of areas, from online lending (WeBank) and insurance (WeSure) to offline medical clinics (Tencent Doctorwork), the company still derives over two-fifths of its revenue from gaming. Its latest big bet in mobile games, “PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds”, has accrued a huge audience of some 50m Chinese gamers who play daily, but because of the monetisation freeze, Tencent cannot cash in.

The government suspension, which began in March without explanation, had been expected to ease in the autumn. Analysts now assume that Tencent will need to tough it out until the second half of 2019. Even once game approvals start up again, the government has said that their number will be limited. To allay Communist Party concerns about the mental and physical health of young gamers, Tencent is also having to curb gaming time and set up a system of user-identity checks.

Capricious regulators may not be wholly to blame for the slowdown in online games, says Steve Chow of Agricultural Bank of China International (ABCI), a Chinese investment bank. Users may simply be spending less time on Tencent’s online entertainment, as other players eat into its market share. For its flagship game, “Honour of Kings”, for example, the average number of daily active users has dropped by a fifth in the past year or so, to 54m in September.

For skittish investors, all this has concentrated minds on whether the giant can maintain its momentum as it enters its third decade. Most agree that gaming will remain an important part of the company, but not its chief driver of revenue growth.

Two concerns are particularly acute. Because its games have done so well, Tencent has been lackadaisical in monetising other parts of its business. It has rightly been nervous about expanding advertising within WeChat, though the service sees unrivalled Chinese mobile traffic of over 1bn monthly active users. Last year Tencent took about one-tenth of total third-party spending on digital ads in China. But Baidu, China’s leading search engine, took 19% and Alibaba, a giant in e-commerce, drew in almost a third.

A second worry is that crimped profits will make it harder for the firm to keep investing heavily in areas outside its core business. Tencent has been backing promising startups in a race with Alibaba to find new users and sources of growth, battling indirectly in areas as varied as food delivery and online education. In some, such as cloud computing, the pair compete directly. Although Tencent’s investors are supportive of this approach, Jerry Liu of UBS, a bank, says the wider tech sell-off stems from a recognition that China’s maturing internet sector is becoming “a zero-sum game”: dominant platforms are having to invest more to stay ahead and so their margins are shrinking.

Tencent’s first internal-restructuring plan since 2012, announced in September, offers a clue to the company’s thinking. In it Tencent set out a long-term shift away from the consumer internet towards business services, marking “a new beginning for the company’s next 20 years”. It has set up a new unit for cloud and “smart” industries, combining all its on-demand software and online services for firms that seek to go digital. Pony Ma, Tencent’s boss, said the “main battlefield” for mobile internet is moving from consumers to companies.

Alibaba, born to bring businesses online through its virtual emporia, has a strong lead in this arena. Last year it took 45% of China’s fledgling cloud-computing market, worth 69bn yuan ($10bn), compared with 10% for Tencent, according to IDC, a research firm. Still, Tencent doubled revenue in cloud services in the second quarter compared with the same period last year. Earnings from “other businesses” (ie, payments and cloud) overtook those from its social networks for the first time.

Mr Chow reckons that Alibaba and Tencent can both create large businesses in cloud computing since the market has lots of room to grow. And Tencent boasts powerful assets. WeChat is on over four in every five Chinese smartphones, so offers a massive market for firms. Last year it introduced a cloud-based platform that allows companies to offer services to users in WeChat via “mini programs” (ie, tiny apps). There are more than 1m mini programs, used by over 200m people every day.

For now, however, its revenue from such mini programs and other built-in services is still “close to zero”, notes David Dai of Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm. Meanwhile rivals have introduced their own offerings of mini programs. Among them is Bytedance, a newish giant that has young Chinese hooked on its flawlessly addictive video and news offerings, curated with artificial-intelligence technology. It is a thorn in Tencent’s side.

In particular, the way in which Bytedance is capturing very young users, as well as young talent, makes Tencent look increasingly grizzled. To increase its appeal to youngsters, Tencent in April revived a short-video app it had shut down, called Weishi, and made it a near-copy of Bytedance’s wildly popular Douyin app.

Pan Luan, a former tech journalist who published a widely-read essay in May contending that Tencent had “no dream”, says the giant looks lumbering at times because “its whole structure is ageing”. Young staff say they have few channels for promotion to decision-making positions, says Mr Pan, and few opportunities to build sparky products, as Tencent spends on stakes in other companies. A young Tencent employee who left to work for a newer tech firm says that pay at firms like Bytedance and Kuaishou, a short-video app (in which Tencent has a stake), is “in another band”, and that they feel more like foreign startups.

Tencent’s outsize influence in China’s online world is ballast that should steady it as it targets business customers. For sheer scale, WeChat seems likely to hold its own. It has given Tencent a powerful distribution channel for its own games, and has allowed it to stymie new rival products, including Douyin, by blocking them from its platform. But the giant is under pressure, and seems to know it. “We have to stay awake,” urged its president, Martin Lau, last month. Such introspection is necessary. Mr Chow says it was thought until this year that “Tencent could win every battle”. With more formidable competitors on the scene, the company will need to pick its fights more carefully.