yikes! —

The Chevrolet Malibu, Honda Accord, Tesla Model 3, and Toyota Camry were all tested.

Not only is the problem of cars killing pedestrians not going away, but the annual death toll over the last decade has actually increased by 35%. The proliferation of cars with automatic emergency braking (AEB) systems that detect pedestrians is therefore a good thing, right?

According to a study by the American Automobile Association, maybe we shouldn’t count on AEB. The association has just tested the pedestrian-detection behavior of four popular mid-sized model-year 2019 sedans—a Chevrolet Malibu, Honda Accord, Tesla Model 3, and Toyota Camry—in a variety of different scenarios. Unfortunately, the results are not promising, particularly when it comes to anything but the least challenging scenarios.

AEB and pedestrian detection are two features that fall under the growing category of stuff we call “ADAS”—advanced driver-assistance systems. ADAS is part of the same technological acceleration that’s driving autonomous vehicle development, but here the goal is to work with a human driver to make them safer. Cameras, automotive radar, ultrasonic sensors, and even lidar inputs are used, on their own or together, so that a car can perceive the world around it and warn its human operator if various safety thresholds are crossed.

In the case of AEB, if a vehicle believes a frontal collision is imminent, it will warn the driver and apply the brakes. This works better at lower speeds—much above 30mph and there simply isn’t time for the system to slow the vehicle sufficiently once it has been triggered. But the data is clear that AEB reduces the number and severity of collisions where one car impacts the rear of another.

The data is so clear that most automakers have made the feature standard well in advance of a government mandate to do so.

Who got run over again and again?

AEB systems with pedestrian detection are less common. These usually use a car’s onboard camera system and computer vision algorithms to detect bipeds in the field of view. They monitor to see if and when those bipeds look as if they’re about to intersect with the vehicle’s forward motion. Although you could get fancy and plunge a real car into a VR environment to test out such functions, it’s much more common to have crash dummies that you can move into the path of an oncoming vehicle. Which is what AAA did when it brought the four vehicles to Auto Club Speedway in Fontana, California.

The testing was all carried out on dry asphalt in a testing area marked out as a four-lane highway with a solid white line dividing the two middle lanes. For one other test, one of the speedway’s surface streets was appropriated: a right turn with a 57-foot (17.3m)-radius curve. Different tests involved adult or child pedestrian targets moving at 3.1mph (5km/h), from left to right across the path of the test vehicle. For each test, the longitudinal distance and the time-to-collision was recorded when each vehicle gave a visual alert that a collision was imminent, as well as once the vehicle began to automatically brake. Impact speed or separation distance were recorded, depending upon the outcome of the test.

How did the cars do on the easy test?

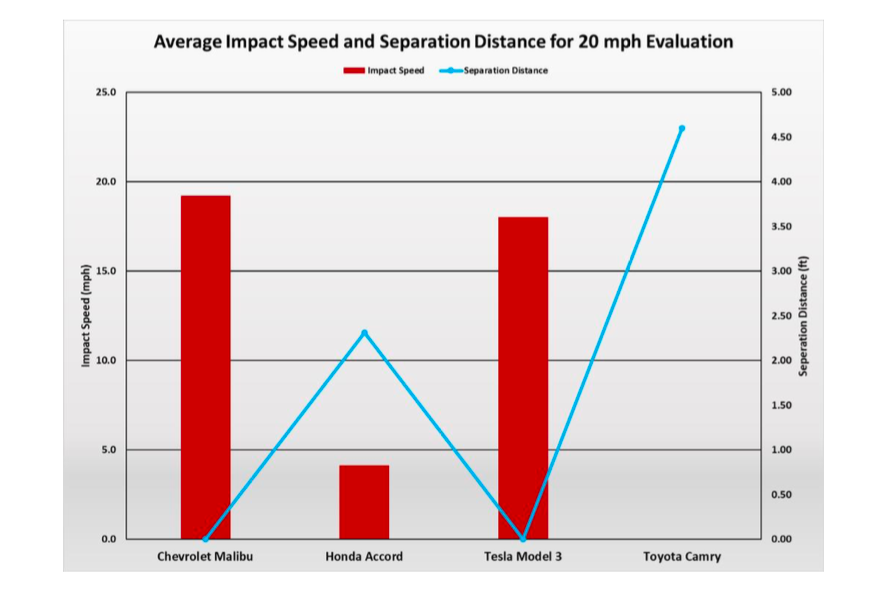

Unfortunately, the results of the tests were very much a mixed bag. For the Chevy Malibu, while it detected the adult pedestrian at 20mph (32km/h) an average of 2.1 seconds and 63 feet (19.2m) before impact, in five tests it failed to actually apply the brakes enough to reduce the speed significantly before each collision took place. The Tesla Model 3 managed little better; it also hit the pedestrian dummy in each of five runs.

On average, the Chevy slowed by 2.8mph (4.5km/h) and alerted the driver on average 1.4 seconds and 41.7 feet (12.7m) before impact. In two runs, there was no braking at all, even though the system detected the pedestrian dummy.

The Honda Accord performed better. Although it notified the driver much closer to the pedestrian (time-to-collision at 0.7 seconds, distance 32 feet/9.7m), it also prevented the impact from occurring in three of five runs and slowed the car to 0.6mph (1km/h) in a fourth.

Best of all was the Toyota Camry. It gave a visual notification at 1.2 seconds and 35.5 feet (10.8m) before impact. But the Camry also stopped completely before reaching the dummy in each of five runs.

AAA

When AAA tried testing each car at 30mph (48km/h), the results were much, much worse. Only the Accord was able to slow by more than 5mph (8km/h) upon detecting the dummy in the 20mph, so it was the only one of the four cars to be subjected to repeated runs at this speed. The Accord did pretty well, slowing to an average of 8mph (12.5km/h), including two instances where it stopped completely. Neither the Malibu, Model 3, or Camry was able to slow more than 5mph when tested at 30mph.

What about more difficult scenarios?

AAA also tested more complicated scenarios. In one setup, two cars were parked next to the test lane, and a child-sized dummy emerged between them into the path of the oncoming car. Each car was tested at least four times at 20mph; if a visual alert was provided on at least one run, a fifth 20mph run was also performed. If a car braked sufficiently during at least three runs at 20mph, the “child steps out from between parked cars” test was performed again at 30mph.

At 20mph, the Malibu only slowed in two out of five runs, and then only by 3.2mph (5km/h). The Model 3 failed to slow down for any of the five runs. But at least the Malibu and Model 3 alerted their drivers; the Camry failed to detect the child pedestrian at all. The Accord did well, avoiding impact completely in two (of five) runs and slowing the car to an average of 7.7mph (12.4km/h).

For the test involving a pedestrian crossing the road shortly after a curve, the results were even more dismal. Here, the Malibu stood out as the only vehicle of the four to even alert the driver, which it did in four out of five runs at an average time-to-collision of 0.4 seconds and a distance to the dummy of 9.5 feet (2.9m). Neither the Honda, Tesla, or Toyota even alerted the driver to the existence of the pedestrian in any of five runs each.

None of the four cars was able to detect a pedestrian crossing the road just after a right turn.

AAA

Pedestrians walking perpendicularly to the flow of traffic (and therefore a car’s sensors) can be more difficult to detect compared to the silhouette of someone walking in profile. Again, the Malibu and Model 3 performed poorly; although both alerted the driver on each run, neither slowed significantly from 20mph. But the Accord and Camry didn’t cover themselves in glory either. At 20mph, the Accord slowed sufficiently to avoid hitting the pedestrian one time out of five, and the Camry managed three out of five. But in the other runs, neither slowed significantly at all.

None of the four cars was able to successfully identify two pedestrians standing together in the middle of the roadway; none alerted its driver or mitigated a crash. And when AAA tested each of the four cars at 25mph in low-light conditions—an hour after sunset with no ambient street lighting, but the car’s low-beam headlights on—none was able to detect a pedestrian to alert the driver or slow the car to prevent an impact.

Which is all to say that your car might come with a clever digital safety net, but it’s far from perfect. If you are behind the wheel of a car, then your job is to pay attention to what’s going on and to not run people over. And this is a reminder to those of us on foot: it’s dangerous out there.