FCC “confused the leash for the dog” —

Judges reluctantly accepted claim that broadband isn’t “telecommunications.”

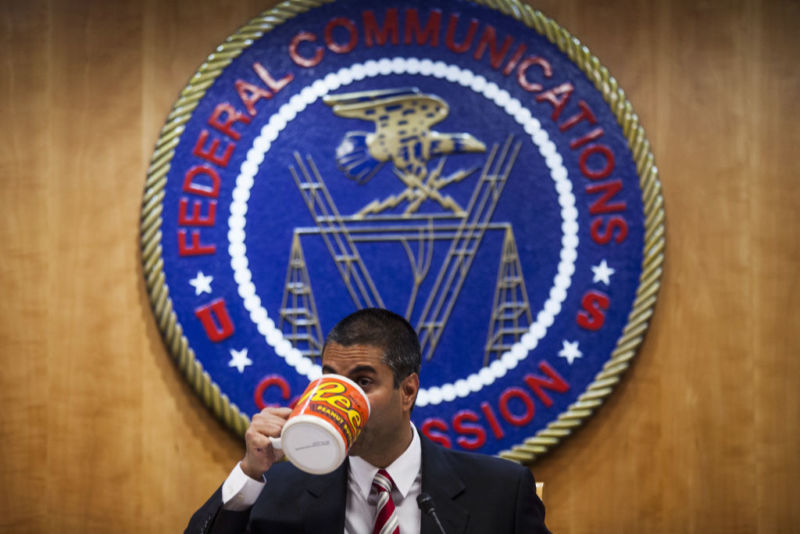

Enlarge / FCC Chairman Ajit Pai with his oversized coffee mug in November 2017.

The Federal Communications Commission has mostly defeated net neutrality supporters in court even though judges expressed skepticism about Chairman Ajit Pai’s justification for repealing net neutrality rules.

One of the three judges who decided the case wrote that the FCC’s justification for reclassifying broadband “is unhinged from the realities of modern broadband service.” But all three judges who ruled on the case agreed that they had to leave the net neutrality repeal in place based on US law and a Supreme Court precedent (see ruling).

The case at the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit turned on the FCC’s decision to reclassify broadband as an information service instead of as a telecommunications service. Telecommunications services are regulated under common-carrier laws, which provided the legal basis for net neutrality rules. The act of reclassifying broadband as an information service deregulated the broadband industry and removed the legal underpinning for the net neutrality rules.

The FCC has broad authority to classify offerings as either information services or telecommunications as long as it provides a reasonable justification for its decision. Judges can disagree with the FCC’s reasoning and still uphold the classification if the FCC provides a good-enough explanation.

To defend the reclassification, the FCC had to explain why broadband fits the federal definition of “information service” and not the federal definition of “telecommunications service.” Under US law, telecommunications is defined as “the transmission, between or among points specified by the user, of information of the user’s choosing, without change in the form or content of the information as sent and received.”

That sounds like what broadband companies provide, but the FCC claims that broadband isn’t telecommunications because Internet providers also offer DNS (Domain Name System) services and caching as part of the broadband package. According to the FCC, the offering of DNS and caching makes broadband an information service, which is defined under US law as “the offering of a capability for generating, acquiring, storing, transforming, processing, retrieving, utilizing, or making available information via telecommunications.”

Judges reluctantly ruled that the FCC made a permissible reading of the statute.

Brand X ties judges’ hands

The Supreme Court’s 2005 decision in the Brand X case, which let the FCC classify cable broadband as an information service, is what basically forced judges to allow the FCC’s new interpretation of broadband. In her concurring opinion, Circuit Judge Patricia Millett explained that Brand X “compels us to affirm as a reasonable option the agency’s reclassification of broadband as an information service based on its provision of Domain Name System (‘DNS’) and caching. But I am deeply concerned that the result is unhinged from the realities of modern broadband service.”

Millett is concerned because the nature of broadband offerings has changed dramatically since Brand X. She wrote:

Brand X was decided almost 15 years ago, during the bygone era of iPods, AOL, and Razr flip phones. The market for broadband access has changed dramatically in the interim. Brand X faced a “walled garden” reality, in which broadband was valued not merely as a means to access third-party content but also for its bundling of then-nascent information services like private email, user newsgroups, and personal webpage development. Today, none of those add-ons occupy the significance that they used to.

Today, consumers use broadband almost exclusively to access third-party content. “In a nutshell, a speedy pathway to content is what consumers value. It is what broadband providers advertise and compete over,” Judge Millett wrote.

While auxiliary services like DNS and caching are still part of the broadband bundle, “their salience has waned significantly since Brand X was decided” in part because DNS is readily available for free from other sources, and “caching has been fundamentally stymied by the explosion of Internet encryption,” Millett wrote.

“For these accessories [DNS and caching] to singlehandedly drive the Commission’s classification decision is to confuse the leash for the dog,” she wrote. In 2019, she continued, “hanging the legal status of Internet broadband services on DNS and caching blinks technological reality.”

Judges defer to Supreme Court

Circuit Judge Robert Wilkins agreed with Millett’s assessment. “As Judge Millett’s concurring opinion persuasively explains, we are bound by the Supreme Court’s decision in [Brand X], even though critical aspects of broadband Internet technology and marketing underpinning the Court’s decision have drastically changed since 2005,” he wrote. “But revisiting Brand X is a task for the [Supreme] Court—in its wisdom—not us.”

Senior Circuit Judge Stephen Williams didn’t join the other two judges in this line of criticism. But the statements from Millett and Wilkins demonstrate why even judges who are skeptical of the FCC’s classification didn’t vote against the agency on this key point. The majority opinion held that classifying broadband as an information service based on the functionalities of DNS and caching is “a reasonable policy choice.”

The court quoted its own 2016 ruling in the case that upheld the Obama-era FCC’s net neutrality order. That case and the current one both upheld FCC classification decisions, even though the FCC decisions themselves were polar opposites.

Yesterday’s court ruling said:

As we said in [the previous net neutrality case], “Our job is to ensure that an agency has acted ‘within the limits of [Congress’] delegation’ of authority,” and “we do not ‘inquire as to whether the agency’s decision is wise as a policy matter; indeed, we are forbidden from substituting our judgment for that of the agency.'”

Decision keeps net neutrality rules off the books

Yesterday’s ruling was issued in response to an appeal filed by a coalition of state attorneys general, consumer advocacy groups, and tech companies such as Mozilla and Vimeo.

Despite upholding the net neutrality repeal and broadband classification, judges remanded the decision to the FCC, forcing the commission to clear up a few points. On remand, the FCC must explain what the repeal means for public safety, for the regulation of pole attachments, and for the Lifeline program that subsidizes phone and Internet access for low-income Americans.

But judges said that the details of the case “weigh in favor of remand without vacatur.” This means that the repeal of net neutrality rules will remain in place even while the FCC deals with the remanded issues.

Judges wrote:

First, the Commission may well be able to address on remand the issues it failed to adequately consider in the 2018 Order… Second, the burdens of vacatur on both the regulated parties (or non-regulated parties as it may be) and the Commission counsel in favor of providing the Commission with an opportunity to rectify its errors. Regulation of broadband Internet has been the subject of protracted litigation, with broadband providers subjected to and then released from common-carrier regulation over the previous decade. We decline to yet again flick the on-off switch of common-carrier regulation under these circumstances.

Why FCC can’t easily preempt state laws

The only big loss for the FCC came during its attempt to prevent all 50 states from passing their own net neutrality laws. Judges vacated the FCC’s attempt at a blanket, nationwide preemption, although the FCC can still try to preempt future laws on a case-by-case basis.

“At bottom, the Commission lacked the legal authority to categorically abolish all 50 States’ statutorily conferred authority to regulate intrastate communications,” judges wrote.

This isn’t a completely free pass for states to regulate broadband providers, but the FCC could still find it difficult to preempt specific laws. The FCC argued that state net neutrality laws would violate a federal policy of non-regulation and that broadband “is an interstate service that should be subject to uniform regulation.”

But the FCC’s opponents argued that the FCC cannot preempt state and local net neutrality laws because the commission abandoned its Title II regulatory authority over broadband. Two of the three judges agreed.

“[I]n any area where the Commission lacks the authority to regulate, it equally lacks the power to preempt state law,” the majority opinion said. The FCC’s “affirmative” sources of regulatory authority come from Title II, III, and VI of the Communications Act, judges wrote. But Pai’s FCC chose to apply Title I to broadband, which contains no such authority.

“It is Congress to which the Constitution assigns the power to set the metes and bounds of agency authority, especially when agency authority would otherwise tramp on the power of States to act,” the majority opinion said. In order for the FCC to preempt state laws using Title I, “the agency’s interpretive authority would have to trump Congress’s calibrated assignment of regulatory authority in the Communications Act,” the opinion said.

Self-made agency policy

The ruling also said that preemption “cannot be a mere byproduct of self-made agency policy” when Congress has not granted authority to preempt. The ruling added that this principle applies “Doubly so here where preemption treads into an area—State regulation of intrastate communications—over which Congress expressly ‘deni[ed]’ the Commission regulatory authority.” (Broadband transmissions consist of both interstate and intrastate communications.)

Judge Williams, who dissented on the preemption ruling, argued that the FCC can preempt state laws even in areas where it isn’t using its “affirmative regulatory authority.” The FCC can develop a “national telecommunications policy” without using its Title II powers over common carriers, Williams wrote.

But the majority said the FCC hasn’t made a showing that wiping out all potential state and local requirements is necessary to achieve the FCC’s deregulatory objectives. If the FCC wants to preempt a specific state law in the future, it will have to “explain how a state practice actually undermines the 2018 Order,” judges wrote. If the FCC “cannot make that showing, then presumably the two regulations can co-exist as the Federal Communications Act envisions.”