You come here often? —

Not to sound like a broken record, but Europe broke records again.

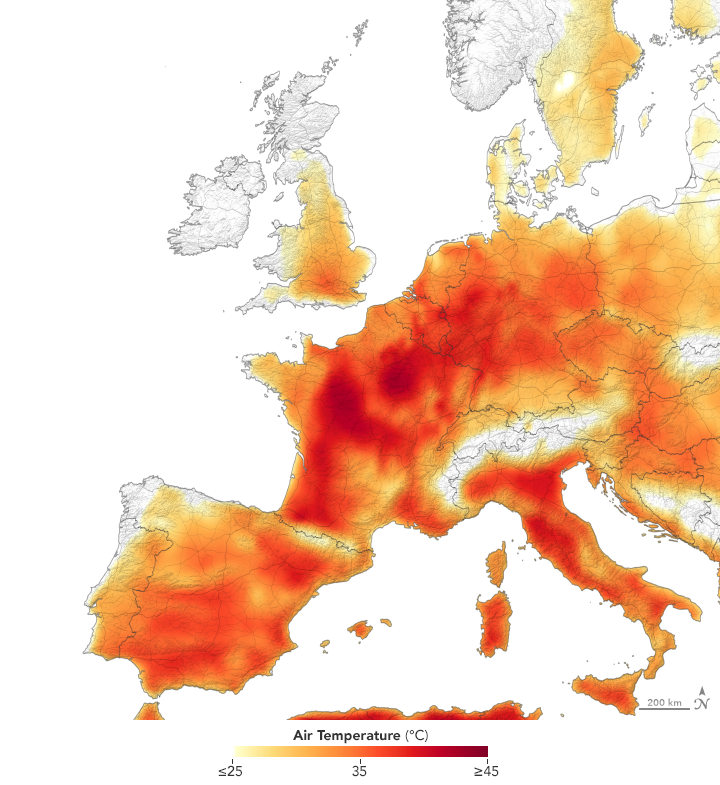

Enlarge / Satellite-estimated surface temperatures for July 25, 2019.

It’s becoming standard procedure that extreme weather events will quickly be analyzed by the World Weather Attribution team—a group of climate scientists who estimate the influence of climate change on individual events. But even so, covering fresh results on a record-breaking European heatwave is jarring, given that we did the same thing just one month ago.

The last week of July saw several days of sweltering heat around Western Europe. Weather stations in Belgium and the Netherlands hit temperatures over 40°C (104°F) for the first time on record, while the UK hit a new high at 38.7°C. Both Paris and Germany set new records at 42.6°C—over 2°C higher than either’s previous high.

The heatwave was the result of a wiggle in the Jetstream helping pull air from North Africa across France and toward Scandinavia. That pattern has happened before, so why did it break so many temperature records this time?

Standardized tests

To look at whether climate change is driving a change in this type of weather in Europe, the researchers employed their standard method. After selecting a handful of locations in these countries, they analyzed historical data for three-day average temperatures, looking for trends in extreme highs. Those trends are clearly there, with higher extreme temperatures in recent decades than were seen in the early 1900s.

The second step is to see whether climate models also simulate that trend in a warming climate but fail to do so in a world without human greenhouse gas emissions. As was the case last month, the researchers found that models tend to underestimate the change in European heatwaves, partly because they are simulating a little more natural variability than we see in the real world. So by combining the change in the observed data and the change in the models, they probably end up with somewhat conservative estimates of how these heatwaves have increased.

Of the locations the team analyzed, France and the Netherlands saw the most extreme event. Even in today’s warmer climate, this is in the neighborhood of a 50-year to 150-year event—meaning that, on average, heatwaves this extreme would only occur once in a 50 or 150-year-period. But if we could travel back to the cooler world of 1900, it would be even rarer. The probability stretches out to well over a once-in-a-millennium event. Or if you prefer, a 50-year or 150-year heatwave back then would have been 1.5 to 3°C cooler than July’s record highs.

Less extreme

For the UK and Germany, the probabilities are a little less extreme. In the current climate, this was a 10-year to 30-year heatwave event, but in 1900, it would have been more like a 100-year to 300-year event.

For either set of countries, the overall point is the same: human-caused global warming is unambiguously leading to more extreme heatwaves in Europe. That’s pretty well established at this point, as the researchers state: “It is noteworthy that every heatwave analyzed so far in Europe in recent years (2003, 2010, 2015, 2017, 2018, June 2019, and this study) was found to be made much more likely and more intense due to human-induced climate change.”

As with the earlier heatwave this year, the team notes that government emergency plans kicked in to help keep people safer in these areas during the hot weather. But as these heatwaves will only continue to increase as long as the climate warms, more adaptation work—particularly in cities—will be required to save lives.