Behold, America: The Entangled History of “America First” and “the American Dream”. By Sarah Churchwell. Basic Books; 368 pages; $19.99. Bloomsbury; £20.

IT IS common for historians to examine the actions of great men. Sarah Churchwell, a professor of American literature at the University of London, does something different. Her protagonists are not people but two expressions: “the American dream” and “America first”. By tracking their usage down the years in newspapers, books and politicians’ speeches, her aim is to cast light not just on the country’s past but also on its politics today. President Donald Trump launched his bid for the White House proclaiming that “the American dream is dead”; he has used “America first” as a rallying cry.

Both phrases are about a century old and have had a richer and more varied life than is commonly realised. The American dream nowadays tends to evoke individuals’ pursuit of riches, Ms Churchwell argues, but it started out in the Progressive Era meaning almost the opposite: “the social dream of justice and equality against individual dreams of aspiration and personal success”. After that, each successive period invented its own American dream according to the prevailing conditions.

For the first 20 years the expression mainly had a political, not an economic meaning. But from the mid-1920s it took on a familiar ring, and in the 1930s, against the background of the Depression, its use exploded as it came to describe what one of its champions, the historian James Truslow Adams, called “that belief in the right and possibility of a better life for all, regardless of class or circumstance”. By the 1950s and the advent of the cold war, says Ms Churchwell, the dream “had shrugged off all sense of moral disquiet, becoming a triumphalist patriotic assertion”.

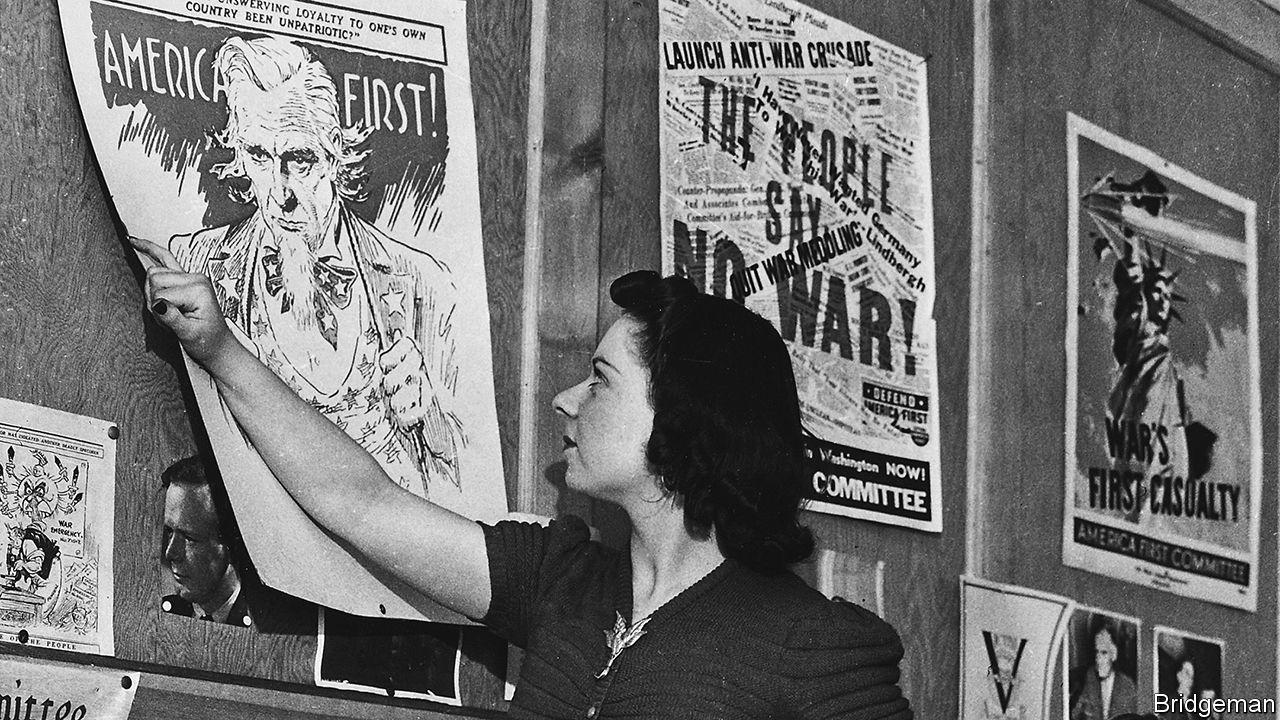

“America first”, meanwhile, has always been a political slogan, with many applications. President Woodrow Wilson tried to wield it with subtlety, explaining that America needed to think of itself first, but to be ready to be Europe’s friend once the first world war was over. Others were cruder, urging protectionism, isolationism or worse. When the nationalist mood took him, William Randolph Hearst slapped “America First” on the masthead of his newspapers. The Ku Klux Klan used it to boost white supremacism.

It has been strikingly popular. The Republican Party adopted it as a catchphrase in 1894. Wilson picked it up in a speech in 1915 and used it as a slogan for his presidential campaign the following year (as did his Republican opponent, Charles Evans Hughes). The next three presidents—Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover—all embraced it. The anti-war America First Committee brandished it. It seems almost an anomaly that “America first” went quiet for so long until its recent thunderous revival.

As she weaves the twin strands of her history, shuttling between the American dream and “America first”, Ms Churchwell sometimes relies on tenuous connections to (and between) her yarns. Books described as “American dream novels” (“The Great Gatsby”, “Of Mice and Men”) turn out not to mention the phrase at all. A juicy tale of Fred Trump, the president’s father, being arrested along with five “avowed Klansmen” at riots in Queens in 1927 has only a tangential connection to the America-first narrative.

Yet this book is timely and instructive. Mr Trump’s critics can be mildly reassured that banging on about “America first” has plenty of precedent; yet they will also be disturbed by the nastiness of some of that history. As for the American dream, Ms Churchwell laments that it has become fossilised and flat. Americans once dreamed more expansively, she says, invoking ideas of social democracy and social justice. For all her evident abhorrence of Mr Trump, she may agree with him on one thing: reviving the dream might help make America great again.