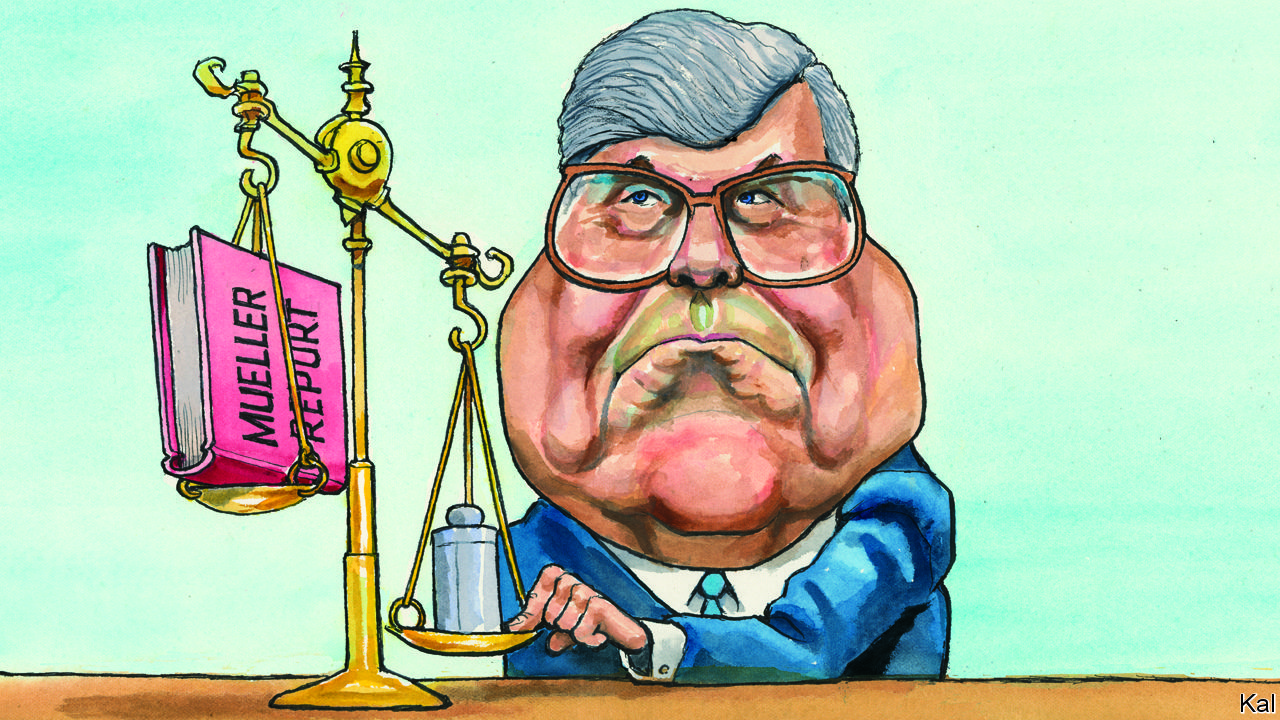

MANY DEMOCRATS are dismayed by Robert Mueller’s failure to take down the president. Yet they have a consolatory new hate figure in the form of William Barr, who began his second spell as attorney-general last month. A grandfatherly 68-year-old, who first presided over the Justice Department for George H.W. Bush, Mr Barr has been castigated for his handling of Mr Mueller’s report, which remains under wraps at his discretion. Jerrold Nadler, Democratic chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, called his summary of the report “a hasty, partisan interpretation of the facts.” Several Democrats running for president, including Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, derided Mr Barr as Donald Trump’s “hand-picked attorney-general” (as if there were any other kind).

This is partly a case of shooting the messenger. Many on the left were convinced Mr Trump was up to his neck in the Russian plot that helped get him elected. They also had an almost cultlike faith in Mr Mueller (the ash-dry prosecutor would be amazed to see how many T-shirts bear his name on campus—as in “Mueller Time—Justice Served Cold!”). The instant Mr Barr relayed the crushing news that the special counsel had found no collusion with Russia by Mr Trump, he was suspected of skulduggery, which seems hysterical. A close friend of the special counsel, Mr Barr is possibly too principled and certainly too canny to have misrepresented his conclusions. If he had done so, they would leak. Yet the attorney-general��s treatment of the second prong of Mr Mueller’s investigation, concerning Mr Trump’s alleged effort to obstruct the various Russia investigations, is more troubling.

It is not clear why Mr Mueller refrained from ruling on the evidence against Mr Trump on this issue. It is also unclear whether he expected Mr Barr to rule for him. Perhaps Mr Mueller felt the decision was above his paygrade, given the Justice Department’s policy of not indicting a sitting president. Perhaps Mr Barr—and his deputy Rod Rosenstein, who supported his view that Mr Mueller had not made a convincing obstruction case—made a straightforward decision. Yet that would make the emphasis Mr Mueller laid upon the possibility of Mr Trump’s guilt—in stressing that his report did “not exonerate” the president—even odder than it already seems. The result, absent further disclosure to provide explanation and reassurance, is just the sort of heaving political mess of intrigue and innuendo Mr Mueller was appointed to clear up.

Whatever they intended, he and Mr Barr have combined to damage Mr Trump while clearing him. Theirs is a jumbled, two-handed version of James Comey’s fateful decision to criticise Hillary Clinton’s email arrangements even as he announced that she would not faces charges. No wonder it has elicited the same partisan response. Republicans consider Mr Trump exonerated, Democrats—almost as understandably—think he hasn’t been.

That is not to imply Mr Mueller considered Mr Trump guilty of obstruction. It will take a fuller disclosure of his report to grasp how “difficult” he considered the factual and legal impediments to that conclusion to be. But it at least seems likely that he wanted his starkly worded equivocation on this issue (which Mr Barr had little option but to relay), to be heard by Congress, which is the only body empowered to hold Mr Trump to account, given that the Justice Department will not. That makes Mr Barr’s final ruling appear unnecessary. Indeed Paul Rosenzweig and others on the Lawfareblog can find no legal or departmental explanation for it.

That alone risks Mr Barr’s intervention seeming partial—at least to the half of America aching to see Mr Trump in irons. And the impression is reinforced by the fact that Mr Barr prejudged the Mueller investigation, in the president’s favour, before he took charge of it. In an unsolicited 19-page memo to Mr Rosenstein last year, Mr Barr argued that the special counsel’s obstruction probe was “fatally misconceived” and “premised on a novel and legally insupportable reading of the law.” Barr boosters argue that one of his strengths as a member of Mr Trump’s cabinet is that he is too old, successful and phlegmatic to be pushed around. His memo, which was distributed to the White House, suggests he was a bit more eager to get back in the game than that portrayal has it.

This is a salutary lesson, especially for those who look to the law to settle political disputes. Democrats—and many Republicans, too—were not wrong to contrast Mr Mueller’s integrity with the president’s lack of it. Yet the special counsel was never likely to be the antidote they craved, because the power of the ballot trumps the law, and because the law is slippery. Mr Trump employs alternative facts; on the question of obstruction, Mr Mueller’s report appears to offer alternative realities.

Obstruction no Barr

The episode also underscores concerns about Mr Barr’s expansive view of executive power. In his memo he argued that the president could not obstruct justice, however malign his motives for a given action, in the lawful performance of his office. In summarising the Mueller report he offered a less radical argument, that Mr Trump could not have obstructed justice because he did not collude with Russia. Yet this seemed so obviously threadbare, given the many Russia-related things Mr Trump had to hide short of a grand conspiracy, that it suggested the extent to which he remains fundamentally guided by extreme deference to presidential authority.

It is a view formed in the 1980s, when conservatives considered the presidency the best means to undo the government expansion of recent years. Almost four decades later, the power of the executive has soared and the ability of lawmakers to hold it to account is at rock-bottom—to the extent that Mr Trump has conducted a two-year war on the Justice Department which most Republican congressmen dare not acknowledge. And yet Mr Barr’s legal and political priorities are unchanged—which is of course why Mr Trump picked him for his job. If dogged consistency is the great virtue of elder statesmen, in changing times it is also their weakness.