THERESA MAY will go to the House of Commons on January 15th expecting defeat. The prime minister’s Brexit deal, hammered out during more than a year and a half of talks in Brussels, has been attacked on all sides of the House. The Labour opposition says it could get a better deal. The Scottish Nationalists and Liberal Democrats are against Brexit of any type. The Democratic Unionists, who normally support Mrs May, cannot abide the deal’s “backstop” arrangement for Northern Ireland. And scores of Mrs May’s own Conservative MPs have said they will vote against the government, most of them because they think the deal would leave Britain too close to the European Union.

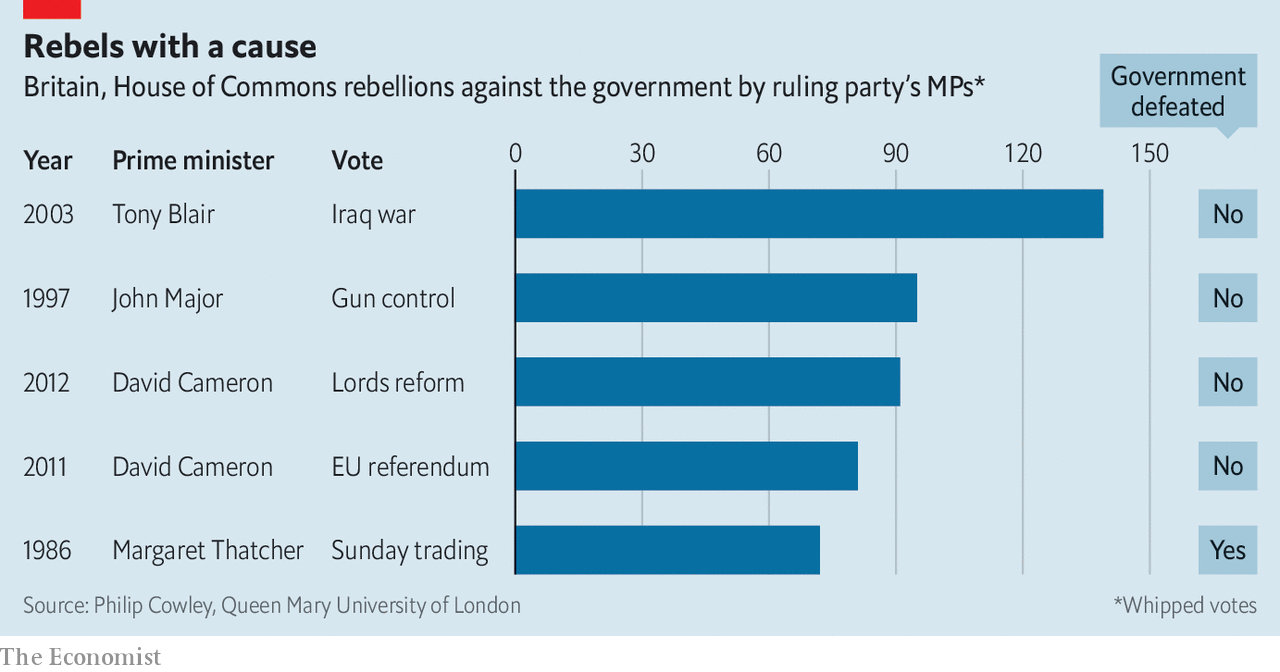

It is likely to add up to a drubbing. But where might it rank in the all-time league of parliamentary flops? Philip Cowley of Queen Mary University of London, an expert on MPs’ revolts, has put together a top-five list of the biggest rebellions in the post-war era (see chart). His list measures the number of votes against the government by its own MPs, rather than the size of the overall defeat (indeed, in four of his top five revolts, the government won with support from the opposition).

Seventy-two Tory MPs have publicly opposed the Brexit deal, according to a count by ConservativeHome, a news site. That would leave Mrs May tied for fifth place with Margaret Thatcher, 72 of whose MPs revolted against her plan to abolish Sunday-trading laws in 1986. But a few dozen more Tories have made unhappy noises about the Brexit deal. The total may climb above 100, perhaps leaving Mrs May in second place behind Tony Blair, who faced a rebellion of 139 over his plan to take Britain to war with Iraq in 2003 (he won the vote anyway, with the backing of the Tories).

The scale of the defeat matters to more than just politics nerds (although, we admit, we are rapt). If Mrs May loses by a narrow margin—fewer than 50 votes overall, say—she might just about be able plausibly to claim that, with a few tweaks, she could get the deal through on a second attempt. The EU is unlikely to agree to any big changes. But a few warm words in the formal political declaration that accompanies the legal text of the agreement might be enough to give wavering Tory rebels a ladder to climb down, should Britain approach its planned departure day on March 29th with no deal in sight.

If, on the other hand, Mrs May loses heavily—by more than 100 votes, for the sake of argument—it is hard to see how further fiddling in Brussels could change enough minds in Parliament to get the deal through. At that point the government would have to consider stronger medicine: a general election, a second referendum or leaving with no deal at all. If she loses the vote, Mrs May must outline her plans to Parliament within three working days, by January 21st. It is looking ever more likely that Britain’s scheduled exit will be delayed. And the odds are also shortening on Britain not leaving at all.