BEFORE SETTING the budget each year, Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer is given a revised set of fiscal forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the official fiscal watchdog. In recent years the chancellor has looked through his fingers as he turned the pages: time and again since the financial crisis of 2008, Britain’s tax revenues have failed to live up to the promise of the OBR’s forecasts. That has made it tricky for the government to reduce the country’s budget deficit.

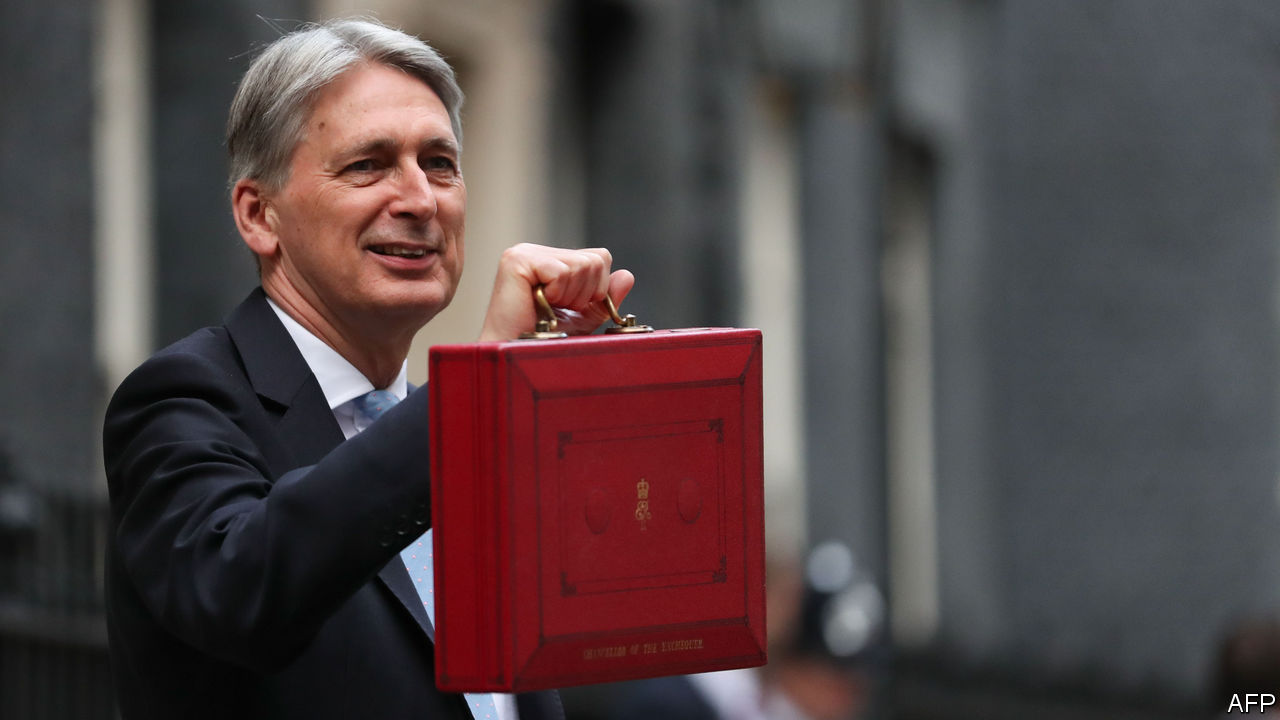

On October 29th, when Philip Hammond delivered his third budget, it was a different story. The OBR had handed him a juicy upgrade in the fiscal forecast. This financial year Britain will borrow just £26bn ($33bn), around 1% of GDP, £10bn less than had been expected back in March. Across the OBR’s forecast period, which runs to 2023, Britain’s public finances are some £60bn healthier than previously believed. On top of that, Mr Hammond had a few innovative tax-raising ideas, including a “digital services tax”, a levy on the revenues which tech giants generate in Britain.

But rather than use all this extra cash to pay down Britain’s public debt, as the Tories’ robust rhetoric on righting the public finances might have suggested, a grateful Mr Hammond splashed out. Theresa May, the prime minister, had already promised more than £20bn of extra spending on the National Health Service, as well as a freeze in fuel duty, costing some £1bn.

In addition to these, Mr Hammond offered up a few sensible spending commitments, including making universal credit, a big welfare reform, somewhat more generous. He also threw some goodies in the direction of MPs who may be wavering over whether to support Mrs May when she presents her hoped-for Brexit deal to Parliament. With all these extra spending commitments, departmental budgets are rising once again, having been on a steady decline for eight years. On that basis, Mr Hammond was able to claim that austerity is “coming to an end”—the political message that Mrs May wants to convey in an attempt to blunt the promise of Labour spending.

In sum, what the OBR giveth, Mr Hammond giveth away. The budget does not much alter the state of the public finances. Mr Hammond is on track to hit his target of reducing Britain’s structural deficit to 2% of GDP by 2021 and thus to ensure that the ratio of public debt to GDP is falling.

The question is whether the economy will stay on this course. Mr Hammond made repeated references to the possibility of a “no-deal” Brexit. That could tip the economy into recession, and would certainly damage the outlook for economic growth. It might not be long before the chancellor is looking through his fingers once again.