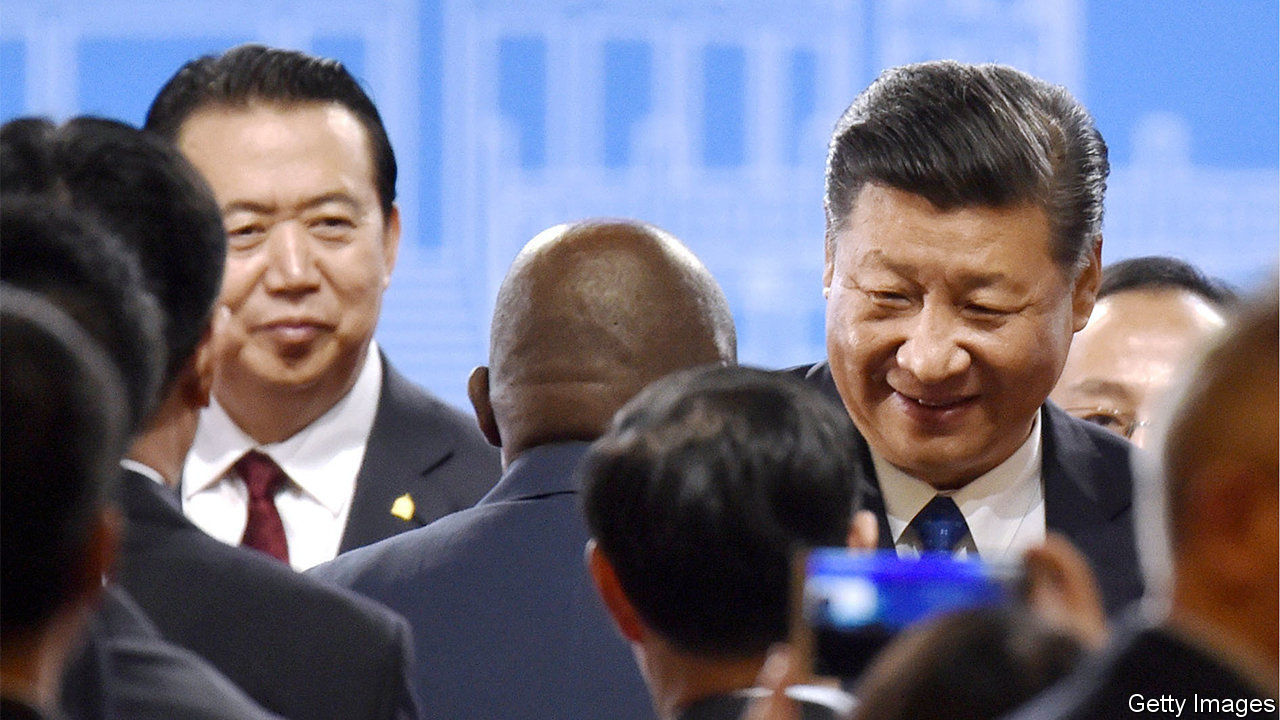

AT A gathering in Beijing last year of Interpol, the body that promotes co-operation between police forces from different countries, the group’s Chinese president, Meng Hongwei (pictured, above left), warned of “political black-swan incidents” that were plaguing the world. He was probably not thinking of his own organisation. But in late September Mr Meng disappeared from public view. Not until days later did China confirm that he had been arrested at home on suspicion of taking bribes and inform Interpol that Mr Meng had resigned. It may be that the cop himself has been caught up in a political storm.

The Chinese government has released no more details of Mr Meng’s alleged crimes. But the way it has handled his arrest suggests that there may be more to it than a suspicion that he was involved in corruption. The Ministry of Public Security, for which Mr Meng still technically works as a vice minister, issued a statement on October 8th saying its Communist Party committee had held a pre-dawn meeting that day. Apart from condemning Mr Meng’s alleged graft, participants stressed the need for “absolute loyalty” (to the party, presumably) as well as “resolute support” for the country’s leader, Xi Jinping. It was agreed that attendees must “maintain a high level of conformity with the political stance, the political direction and the political principles of the party centre with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core.” Had Mr Meng erred in this respect, too?

There was no sign of it two years ago when Mr Meng became the first Chinese citizen to be appointed as Interpol’s president. That was regarded by Chinese officials as a welcome affirmation of China’s growing global power, and as an opportunity to secure greater international support for China’s efforts to secure the return of corrupt officials who had fled abroad—an important part of Mr Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. At last year’s Interpol gathering in Beijing, Mr Meng stood next to Mr Xi for the official group photograph. It was as strong a declaration of the party’s confidence in Mr Meng that he could have received.

In April, however, there was a hint of possible trouble. It was announced that Mr Meng was no longer a member of his ministry’s party committee. Last month, after he flew back to Beijing from France where Interpol is based, his wife, Grace Meng, received a three-character message from his WhatsApp account: “Await my call”. And then four minutes later, an emoji popped up from the same sender. It was of a dagger. Ms Meng told reporters in France that she interpreted this as a sign that her husband was in danger. She heard no more. Ms Meng and the couple’s two children are now under French police protection.

If the case does involve murky politics in Beijing, there is little to suggest of what kind. At the public-security ministry’s meeting, there was a possible hint in a reference made to the need to “eliminate the pernicious influence” of Zhou Yongkang, a retired security chief who was jailed for life in 2015 for corruption and abuse of power. Mr Zhou’s case clearly involved more than just graft. Referring to him and other high-ranking jailed officials, Mr Xi said in 2016 that senior people in the party had engaged in “political conspiracies”.

Mr Meng was promoted to vice minister in 2004, when Mr Zhou was the minister. But if the two men had had close personal links, it is unlikely that Mr Meng would have been put forward by China for the job at Interpol after Mr Zhou’s imprisonment. Grace Meng has said that she, too, is keen to find out more. “From now on, I have gone from sorrow and fear to the pursuit of truth, justice and responsibility toward history,” she told journalists. “This is political ruin and fall!” she said in a text message to the Associated Press, a news agency. Overseas Chinese-language media are awash with speculation about what secrets she herself might know, and whether she might use them to bargain with the party for lenient treatment for her husband.

What is certain is that Mr Meng’s case is in the hands of politicians. It is the party’s leaders who decide which senior officials to jail. “These are the best of times, and the worst of times,” Mr Meng said at last year’s Interpol gathering, loosely quoting Dickens. His worst have probably just begun.