SOME states soothe their citizens in troubled times. Others prefer not to sugar-coat things. “A larger European conflict could start with an attack on Sweden,” warned the most recent report of the country’s defence commission. Electricity would be limited. Calorie intake would fall. Tens of thousands might be wounded. This was not idle talk: in June, all 22,000 Swedish volunteer soldiers were called up for the largest surprise exercise since 1975. For the first time in almost 30 years, the government has written to millions of households exhorting them to prepare for the worst. “We will never give up,” warned leaflets decorated with vivid tableaux of burning buildings and rolling tanks.

Sweden’s aim is to hold out for three months, until help arrives. These twin tasks—becoming “indigestible to Russia”, as one analyst puts it, and ensuring that the cavalry shows up—will be high on the agenda of whichever government emerges from the hung parliament produced by the election of September 9th. Sweden may not be a member of NATO. But under Stefan Lofven, Sweden’s Social Democratic prime minister for the past four years, it has manoeuvred as close to the alliance as it is possible to get from the outside. By deferring the question of outright membership, anathema to the left, he created political space to tighten Sweden’s triple embrace of America, NATO and its neighbours. A landmark “host nation” agreement with NATO was steered through parliament in 2016. America’s potential wartime role in Sweden was once a state secret; now contingency plans can be made openly.

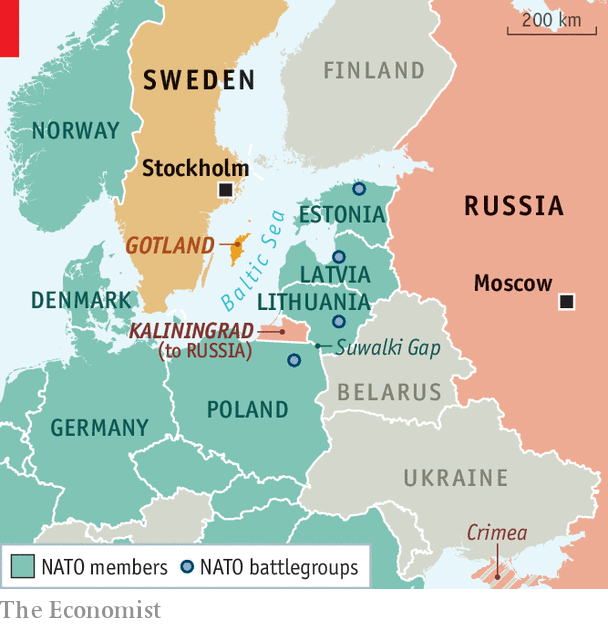

This is not just for Sweden’s benefit. Thousands of NATO troops were sent to the Baltic states last year to serve as tripwires in case of any Russian aggression. In a war, they would need swift and massive reinforcement. But the overland route runs through the Suwalki Gap, a choke point with the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad on one side and Russia’s ally Belarus on the other. It would be easier to send backup through Sweden and over the Baltic Sea. That is one reason why Gotland, a bucolic Swedish island in the middle of those waters, has assumed such importance. Were Russia to seize it the sea route might also become perilous. Last year’s Aurora exercise, involving the largest ever American force on Swedish soil, simulated attacks on Gotland. In January, Sweden re-established a military unit there, its first new regiment since the second world war.

Sweden is also cosying up to its neighbours. It agreed to swap defence attachés with Norway last year, and to share data on air surveillance—particularly Russian bombers on the prowl. It has gone further with Finland, agreeing to form a “partially integrated” Finnish-Swedish air force and operating a joint naval group that lets Finnish admirals command Swedish vessels, and vice versa. Niklas Granholm of FOI, Sweden’s defence research agency, notes that Swedish, Finnish and Norwegian fighter pilots are on a first-name basis after weekly air exercises in the High North. He suggests this could be turned into a “strike force for the entire Nordic-Baltic region”.

Whether the Social Democrats cling to power or are ousted by the centre-right Moderates in the coming months, a consensus has taken hold. “We are realising that Crimea was not a passing storm, but climate change,” says Anna Wieslander, director of the Swedish Defence Association, referring to Russia’s annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula in 2014. One left-wing MP milling around Sweden’s parliament, the Riksdag, is glum. “Nothing will change,” he complains of the election. “Everyone hates Russia.”

In fact, Sweden’s political direction will have important implications for defence. The four opposition parties that governed until 2014, including the Moderates, have all come out in favour of joining NATO over the past few years. Polls indicate public support swinging modestly in this direction: 43% in favour and 37% against. But there are several hitches.

One decision for the next prime minister is whether to sign a UN treaty “banning” nuclear weapons. Some Social Democrats, including Margot Wallström, the foreign minister, are keen. But it would strain Sweden’s relationship with America and NATO. A more serious obstacle is that any Moderate effort to take Sweden into NATO might depend on the support of the far-right Sweden Democrats. The party is opposed to membership on nationalist grounds, though its base, numbering many former Moderate voters, might be more amenable. A third problem is that Sweden is reluctant to leave Finland in the lurch, if its smaller neighbour declines to join. Meanwhile, as the wrangling continues, Sweden hugs NATO ever-tighter: over 2,000 of its troops will join one of NATO’s largest-ever exercise next month.