THE one thing everyone knows about insurance is, read the fine print. Indians should take heed as Narendra Modi, the prime minister, rolls out what he is trumpeting as the world’s biggest health-insurance plan. Ayushman Bharat, meaning Long-Life India, aims to install a safety-net for the poorest half-billion of India’s 1.3bn citizens, which is to say, for a big portion of the poorest people in the world. From now on, the government promises, any family that fits broad criteria of need will be eligible to receive nearly $7,000 a year in hospital expenses without paying a penny themselves. Instead, the state will pay premiums to private insurers; eligible patients can seek treatment at any institution, public or private, that has joined the scheme.

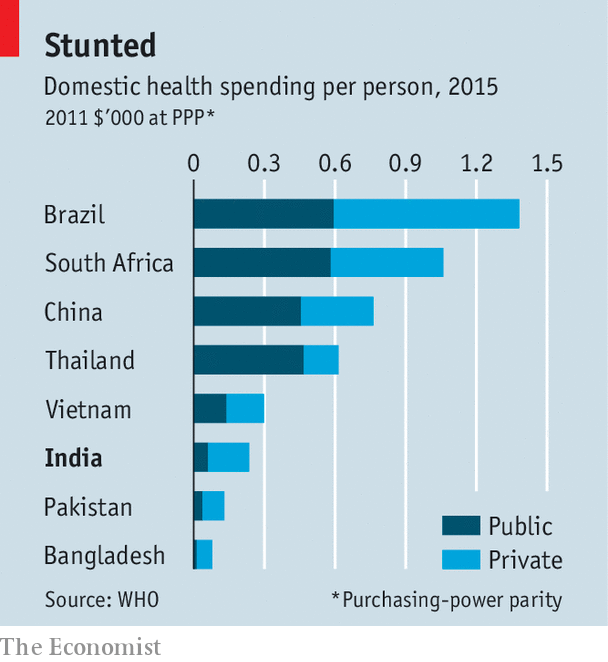

There is no doubt that Ayushman Bharat will bring immense relief to many. Only a third of Indians now have any medical insurance, and government spending on health, equivalent to a measly 1.1% of GDP, accounts for a low 25% of health spending. The government spends far less on health care than its counterparts elsewhere in the developing world (see chart). An analysis by Mint, a financial newspaper, suggests that every year some 36m families, or 14% of households, face an unexpected medical bill equal to the entire annual living expenses of one member of the family. All too often such surprise costs are enough to tip families into penury.

Past government schemes have tried to tackle this problem, but with far lower limits on payouts. They have nonetheless been plagued by administrative troubles, understaffing and wide-scale fraud perpetrated by hospitals, insurance companies and patients themselves. Studies show that families who availed themselves of public insurance ended up spending more of their own funds on health than those with no coverage, partly because of follow-up costs such as medicines, but also because people felt less need to economise, and started treating conditions they would previously have just endured.

Ayushman Bharat is intended to replace and vastly expand previous programmes. Proponents note potential benefits that go beyond reducing misery for the downtrodden. The scheme, they say, aptly reflects the reality that private care now dominates Indian medicine, yet it also seeks to pool risk so as to reduce insurance premiums and use the huge number of patients to drive down the cost of procedures. The creation of a new class of consumers should encourage the building of hospitals where they were previously uneconomic, especially in remote rural areas.

For critics who question the focus on inpatient treatment, rather than primary or preventive care, government boosters point to Ayushman Bharat’s commitment to create some 150,000 public “health and wellness centres” across the country. These are supposed to provide initial diagnoses and outpatient services, feeding patients who need hospital care into the insurance scheme.

But detractors have other reasons to detract. For one thing, the initiative looks as woefully underfunded as previous efforts. The insurance scheme’s first-year budget amounts to a miserly $300m (0.01% of GDP), hardly the “world’s biggest” and indeed not substantially more than was previously budgeted for health insurance. Indu Bhushan, the CEO of Ayushman Bharat, insists that this will rise rapidly to perhaps $1.5bn a year.

Public-health experts concur that a measured expansion, with plenty of room for trial and error, makes more sense than a huge initial splurge. But even then, funding would amount to less than what Mr Modi recently doled out to India’s ailing, but politically potent sugar industry. If just one in ten of the 36m families facing shock medical bills every year made full use of the scheme, hospitals would be demanding closer to $25bn in fees.

That may seem an over-estimate, but the experience of previous insurance schemes suggests that once patients do not need to worry any more about the cost, those who might have put up with pains, or turned to informal doctors, eagerly embrace more elaborate treatment. In any case, given the paucity of data that insurers need to set rates, and given the bargain-basement prices that the government is offering to hospitals that sign onto the scheme ($550 for inserting a cardiac stent, for example), it may take years of bargaining and tinkering to devise a workable financial model. And paying for health care via insurance might prove more expensive to the state than providing it directly.

As for the health centres, these in fact already exist, having been built by previous governments as village clinics. Most are now defunct or woefully under-used. They are simply being renamed, says Jean Dreze, an economist, who notes that the budget earmarked for them would barely cover the cost of fresh paint. Jishnu Das of the Centre for Policy Research, a think-tank in Delhi, is puzzled by the decision to tart up derelict clinics. “Policymakers say that instead of improving the places where people actually go to seek primary care—community health centres, public district hospitals and informal private providers—we should try to improve the places where they don’t go. That is extremely convoluted logic.”

What is not convoluted is the politics of announcing a giant, transformational health programme, which may prove a life-giving gift for millions of poor families, six months before a general election. You do not need to read the fine print to figure that out.