EVERY other Tuesday at Facebook, and every Friday at YouTube, executives convene to debate the latest problems with hate speech, misinformation and other disturbing content on their platforms, and decide what should be removed or left alone. In San Bruno, Susan Wojcicki, YouTube’s boss, personally oversees the exercise. In Menlo Park, lower-level execs run Facebook’s “Content Standards Forum”.

The forum has become a frequent stop on the company’s publicity circuit for journalists. Its working groups recommend new guidelines on what to do about, say, a photo showing Hindu women being beaten in Bangladesh that may be inciting violence offline (take it down), a video of police brutality when race riots are taking place (leave it up), or a photo alleging that Donald Trump wore a Ku Klux Klan uniform in the 1990s (leave it up but reduce distribution of it, and inform users it’s a fake). Decisions made at these meetings eventually filter down into instructions for thousands of content reviewers around the world.

Seeing how each company moderates content is encouraging. The two firms no longer regard making such decisions as a peripheral activity but as core to their business. Each employs executives who are thoughtful about the task of making their platforms less toxic while protecting freedom of speech. But that they do this at all is also cause for concern; they are well on their way to becoming “ministries of truth” for a global audience. Never before has such a small number of firms been able to control what billions can say and see.

Politicians are paying ever more attention to the content these platforms carry, and to the policies they use to evaluate it. On September 5th Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s number two, and Jack Dorsey, the boss of Twitter, testified before the Senate Select Intelligence Committee on what may be the companies’ most notorious foul-up, allowing their platforms to be manipulated by Russian operatives seeking to influence the 2016 presidential election. Mr Dorsey later answered pointed questions from a House committee about content moderation. (In the first set of hearings Alphabet, the parent of Google, which also owns YouTube, was represented by an empty chair after refusing to make Larry Page, its co-founder, available.)

Scrutiny of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube et al has intensified recently. All three faced calls to ban Alex Jones of Infowars, a conspiracy theorist; Facebook and YouTube eventually did so. At the same time the tech platforms have faced accusations of anti-conservative bias for suppressing certain news. Their loudest critic is President Donald Trump, who has threatened (via Twitter) to regulate them. Straight after the hearings, Jeff Sessions, his attorney-general, said that he would discuss with states’ attorneys-general the “growing concern” that the platforms are hurting competition and stifling the free exchange of ideas.

Protected species

This turn of events signals the ebbing of a longstanding special legal protection for the companies. Internet firms in America are shielded from legal responsibility for content posted on their services. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 treats them as intermediaries, not publishers—to protect them from legal jeopardy.

When the online industry was limited to young, vulnerable startups this approach was reasonable. A decade ago content moderation was a straightforward job. Only 100m people used Facebook and its community standards fitted on two pages. But today there are 2.2bn monthly users of Facebook and 1.9bn monthly logged-on users of YouTube. They have become central venues for social interaction and for all manner of expression, from lucid debate and cat videos to conspiracy theories and hate speech.

At first social-media platforms failed to adjust to the magnitude and complexity of the problems their growth and power were creating, saying that they did not want to be the “arbiters of truth”. Yet repeatedly in recent years the two companies, as well as Twitter, have been caught flat-footed by reports of abuse and manipulation of their platforms by trolls, hate groups, conspiracy theorists, misinformation peddlers, election meddlers and propagandists. In Myanmar journalists and human-rights experts found that misinformation on Facebook was inciting violence against Muslim Rohyinga. In the aftermath of a mass shooting at a school in Parkland, Florida, searches about the shooting on YouTube surfaced conspiracy videos alleging it was a hoax involving “crisis actors”.

In reaction, Facebook and YouTube have sharply increased the resources, both human and technological, dedicated to policing their platforms. By the end of this year Facebook will have doubled the number of employees and contractors dedicated to the “safety and security” of the site, to 20,000, including 10,000 content reviewers. YouTube will have 10,000 people working on content moderation in some form. They take down millions of posts every month from each platform, guided by thick instruction manuals—the guidelines for “search quality” evaluators at Google, for example, run to 164 pages.

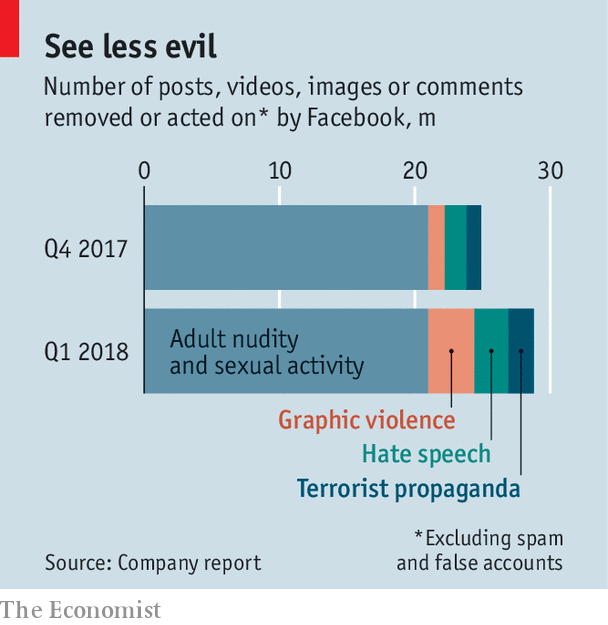

Although most of the moderators work for third-party firms, the growth in their numbers has already had an impact on the firms’ finances. When Facebook posted disappointing quarterly results in July, causing its market capitalisation to drop by over $100bn, higher costs for moderation were partly implicated. Mark Zuckerberg, the firm’s chief executive, has said that in the long run the problem of content moderation will have to be solved with artificial intelligence (AI). In the first three months of 2018 Facebook took some form of action on 7.8m pieces of content that included graphic violence, hate speech or terrorist propaganda, twice as many as in the previous three months (see chart), mostly owing to improvements in automated detection. But moderating content requires wisdom, and an algorithm is only as judicious as the principles with which it is programmed.

At Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, executives instinctively resist making new rules restricting content on free-speech grounds. Many kinds of hateful, racist comments are allowed, because they are phrased in such a way as to not specifically target a race, religion or other protected group. Or perhaps they are jokes.

Fake news poses different questions. “We don’t remove content just for being false,” says Monika Bickert, the firm’s head of product policy and counterterrorism. What Facebook can do, instead of removing material, she says, is “down-rank” fake news flagged by external fact-checkers, meaning it would be viewed by fewer people, and show real information next to it. In hot spots like Myanmar and Sri Lanka, where misinformation has inflamed violence, posts may be taken down.

YouTube’s moderation system is similar to Facebook’s, with published guidelines for what is acceptable and detailed instructions for human reviewers. Human monitors decide quickly what to do with content that has been flagged, and most such flagging is done via automated detection. Twitter also uses AI to sniff out fake accounts and some inappropriate content, but it relies more heavily on user reports of harassment and bullying.

As social-media platforms police themselves, they will change. They used to be, and still see themselves as, lean and mean, keeping employees to a minimum. But Facebook, which has about 25,000 people on its payroll, is likely soon to keep more moderators busy than it has engineers. It and Google may be rich enough to absorb the extra costs and still prosper. Twitter, which is financially weaker, will suffer more.

More profound change is also possible. If misinformation, hate speech and offensive content are so pervasive, critics say, it is because of the firms’ business model: advertising. To sell more and more ads, Facebook’s algorithms, for instance, have favoured “engaging” content, which can often be the bad kind. YouTube keeps users on its site by offering them ever more interesting videos, which can also be ever more extreme ones. In other words, to really solve the challenge of content moderation, the big social-media platforms may have to say goodbye to the business model which made them so successful.