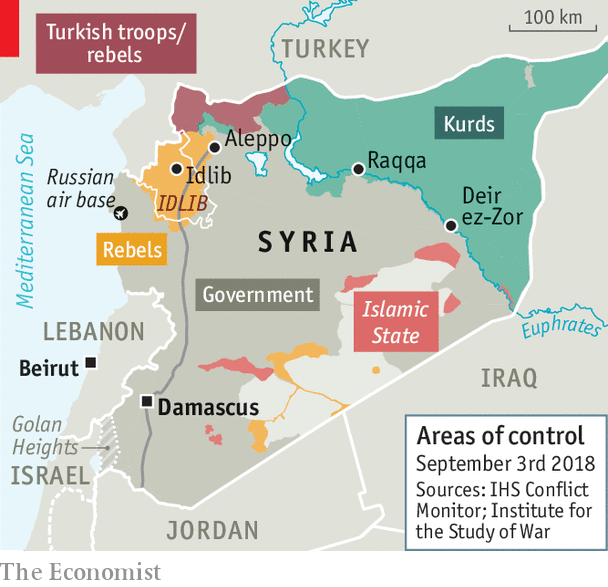

THE Syrian regime and its Russian backers may soon launch one of the biggest battles of the war. The signs are ominous. Thousands of regime troops are massing at the gates of Idlib province, the rebels’ last bastion. Russia has dispatched more warships, bombers and fighter jets to Syria. On September 4th Russian jets struck targets in the south of the province. Meanwhile, Turkey is sending tanks to its border and reinforcing its outposts within Idlib. The rebels (pictured above) are blowing up bridges, digging trenches and expanding their network of underground tunnels. Turkey, which backs the opposition, has told rebel leaders to expect an assault within weeks.

A full-blown offensive would be catastrophic. Idlib is home to 2m-3m civilians. The fighting would drive many from their homes. But after a succession of regime victories in recent months, the noose has tightened around Idlib, leaving its inhabitants with nowhere to run. Those who try to find sanctuary in Turkey risk being shot by Turkish soldiers.

Syria’s recent offensives on rebel-held suburbs and cities provide some idea of the horror that awaits Idlib. Russian warplanes, and some from Syria’s depleted fleet, will probably pummel entire neighbourhoods with the aim of driving out civilians and denying rebels the cover of buildings. In the battle last year for Mosul, an Iraqi city of less than 1m, the American-led coalition killed at least 1,000 civilians despite using mainly precision-guided, or “smart”, bombs. Idlib, whose population is three times larger, will face Russian bombs that are almost entirely unguided, or “dumb”, meaning they are quite likely to miss their targets and instead hit civilians.

Once Idlib has been softened up from the air, a grinding ground offensive would follow, led by Syrian troops and assorted militiamen as well as special forces from Russia and Iran. Some of the troops massing around Idlib are former rebels who surrendered to the regime in other battles, a sign of both the government’s manpower shortage as well as the sense of impending defeat among rebels. The attacking troops will probably use indiscriminate weapons, such as incendiary and cluster bombs, as well as heavy armour.

The few hospitals and clinics still operating would struggle to cope with the large number of casualties expected. Supplies of food and medicine from Turkey may be cut off. UN officials warn that an offensive by the regime would trigger the worst humanitarian emergency of the war.

None of this worries the regime. The battle may prove to be one of the conflict’s bloodiest, but it may also be its last and spell the end of the armed rebellion against Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad. And it would give the regime control of the north-south highway, a vital trade route.

Whether and when such an assault takes place depends largely on the outcome of talks between Russia and Turkey. Although the two countries back opposing sides, both would prefer to avoid a full-scale offensive. For Turkey, which already hosts 3.5m Syrian refugees, a further exodus would add pressure to its struggling economy. It worries, too, that the fall of Idlib could send jihadists, including a large number of Western and other foreign fighters, across its borders.

Russia, meanwhile, is trying to persuade the West to stump up cash to rebuild the country it has helped destroy. It argues that most of Syria is now safe enough for refugees to start returning. A major offensive that kills thousands of civilians and damages hospitals and schools would do little to strengthen its case. Russia also hopes to avoid a wider rift with Turkey.

The way to avert an onslaught, in Russian eyes, is to convince the rebels to surrender. This tactic has worked in smaller towns and cities where rebels have laid down their weapons in return for amnesty. Idlib, however, is different. It is home to the regime’s fiercest opponents, an assortment of some 70,000 jihadists and Islamists and more moderate rebels. Many were bused to Idlib from other fronts precisely because they refused to reconcile with the regime.

Among them are fighters aligned with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which controls about 60% of Idlib. It is a former al-Qaeda affiliate and is led by jihadists who are wanted by the world’s intelligence services and reviled by almost everyone. Its people are more likely to fight to the death than surrender.

Officials with the other big rebel factions say talks with Russian officers have gone nowhere. Fear is a factor. In recently recaptured parts of the country, the regime’s goons have been arresting former rebels and opposition officials who were promised amnesty. Some have disappeared into Mr Assad’s torture dungeons. “The Russians aren’t offering anything. It’s either die, or surrender and then die,” says one official. The rebels have also arrested hundreds of people in the areas they control on charges of negotiating with the Russians and the regime. HTS has erected gallows on the roundabout of one town in Idlib, to warn those who may want to abandon the fight.

Turkey’s efforts to splinter HTS by peeling away more moderate fighters have yielded little. Yet it has so far resisted Russian calls to confront the jihadists head on, since it fears they may retaliate violently on Turkish soil. Instead it has tried to persuade HTS to disband. But Russia’s patience is wearing thin. Drones launched from Idlib continue to attack Russia’s airbase in Latakia.

Turkey may be willing to agree to a limited Russian-backed offensive against HTS in the south and west of Idlib province. On August 31st it declared the group a terrorist organisation, a sign that negotiations with it may have broken down. But such a limited operation may not be enough to satisfy Russia and Mr Assad, since it would leave the main north-south highway outside the regime’s control.

The leaders of Turkey, Russia and Iran are due to meet on September 7th. It may be their last chance to work out a deal that spares Idlib from wholesale slaughter.