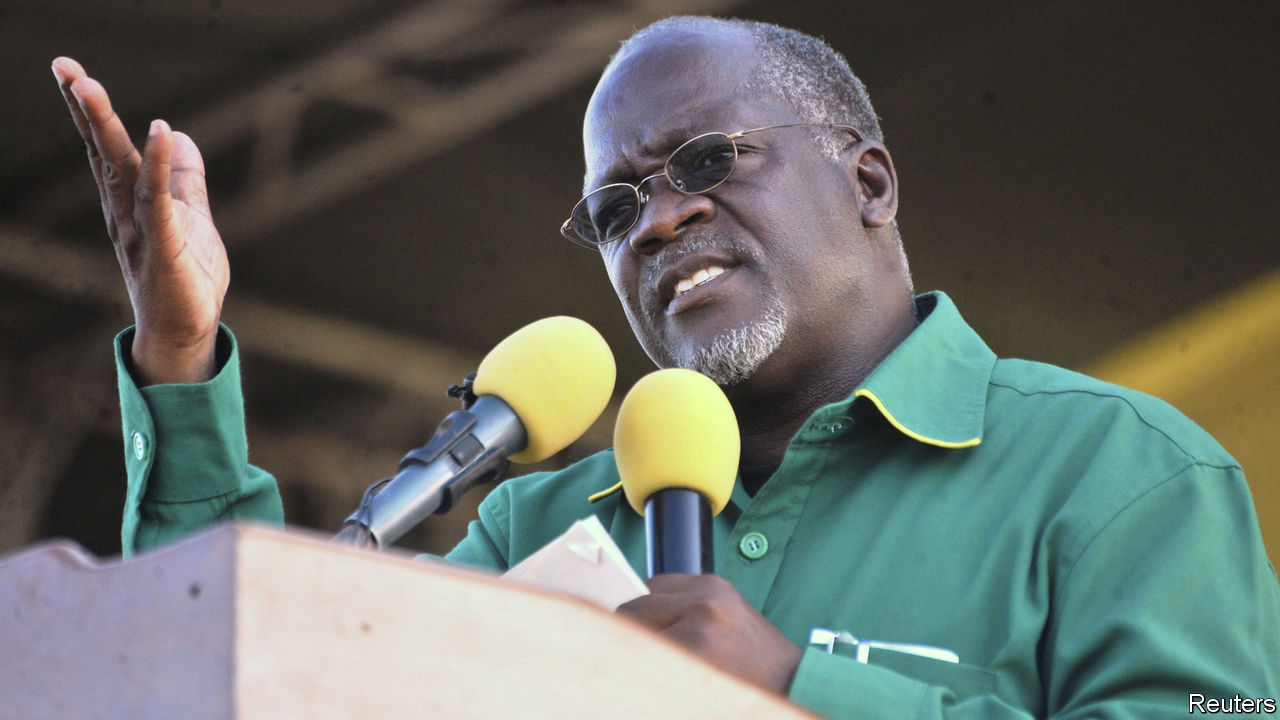

PAUL MAKONDA seems a lot more like a flailing moral crusader than the regional commissioner of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s commercial capital. The 36-year-old has come up with a variety of schemes to catch the eye of his patron, President John Magufuli (pictured). One is clamping down on supposed vices such as smoking shisha and sleeping in past 8am. His latest pledge, to set up a homophobic “surveillance squad” to track down those guilty of homosexuality, which is illegal, is by far his nastiest.

It has also alarmed the West. On November 5th, the EU recalled its ambassador, citing a deterioration in human rights and the rule of law. The rot began soon after Mr Magufuli was elected in 2015 and has recently worsened. Today Tanzania is on the descent from patchy democracy towards slapdash dictatorship.

Barely a week passes without brazen displays of arbitrary power. On November 1st Mr Magufuli appeared at what was billed as a “public debate” on his record after three years in office. It was no such thing: the president sat on a stately chair in the audience at the University of Dar es Salaam while sycophantic academics praised his tenure. Conveniently for Mr Magufuli, an opposition politician, Zitto Kabwe Ruyagwa, was arrested the night before and charged with sedition, so could not attend.

Other foes have met similar fates. Opposition members of parliament who refuse to accept bribes (the going rate is 60m shillings, or $26,200) to cross the aisle and join Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), the ruling party, are arrested. According to a lawyer who has represented opponents of the regime, every opposition MP who has rejected a bung has a pending charge against them. Last year Tundu Lissu, an MP, was shot and injured outside his home. This makes people scared to hold the president to account.

So too does legislation that outlawed the dissemination of any “statistical information” that may “invalidate, distort, or discredit official statistics”. The change follows the publication of an annual survey into political attitudes by Twaweza, a local research group. In 2016 it found that 96% of Tanzanians approved of Mr Magufuli. In 2017 the share was 71%; in July it was 55%. That is a poor showing in a country where CCM has never lost an election. Aidan Eyakuze, the group’s director, has yet to get back his passport, which was confiscated days after publication of the survey.

Another reason for the law concerns economic data. Tanzania’s GDP grew on average by about 6.5% per year over the past decade. But under Mr Magufuli the private sector has been subject to relentless shakedowns by tax collectors. Several prominent businessmen have been arrested on trumped-up charges of money laundering, a crime which is ineligible for bail. Though the government insists the economy is still expanding at its former pace, other economic data, such as slowing credit growth and rising bad debts, suggest otherwise.

Some worry that a slowing economy may lead to further repression and obfuscation of data, causing yet more economic harm. Though the EU has raised an alarm, other international institutions, such as the World Bank, are staying quiet. Tanzania, which receives more aid money per person than any other African country, has been a darling of donors since the 1990s, when it seemed to be consolidating its democracy and also reducing poverty. Yet after a decade or so during which freedoms began to flourish, Tanzanians are facing both economic hardship and repression.